Curiosity may have killed the cat but it’s the life blood of the policy officer

Being curious is a critical part of being a policy officer and our number one curiosity tool is asking questions.

Asking questions however can be daunting. We may be afraid to expose what we don’t know, maybe we don’t know who to ask or we know who they are though don’t know how to access them. We may have been brought up understanding it was impolite to ask questions. Or perhaps we think we know everything there is to know about a policy; trust me, we don’t. Bottom line - we can’t afford to not ask questions.

Discovering a wealth of information:

We discover a wealth of information by asking questions. Stakeholders (aka people) give us access to data that we may not have considered or even been aware of by sharing their knowledge, their expertise, and their lived experiences. Their answers to our questions may support the data we have and they may challenge the premise to the policy commitment. This is all important data. Why? Because when we have the data we need, we can proceed to the next step of considering and analysing the collated data.

When is enough enough:

This can open another potentially unnerving prospect. How much information is enough. I’m not aware of an easy-to-use system that identifies when enough information has been collated (please share if you know of one and I’m serious about the easy-to-use bit!). However, information or data saturation will be reached. This is when themes start to emerge from the growing information treasure trove and nothing new or different is being shared.

Planning for questions:

Let’s go back a couple of steps to think about the planning required to make sure you’re asking the right questions. The below checklist will be useful for you and your policy team.

1. Do we understand the issue we are trying to solve or the opportunity that we are trying to embrace?

2. Are we able to describe the policy commitment and the context in which the commitment was made?

3. Do we fully understand the change the policy is intended to make?

4. Can we articulate ‘what good looks like’?

5. What is it that we need to understand - the who, what, when, how and why?

6. Are we clear about what’s in scope and what’s out of scope?

7. Are we clear about what we know through evidence informed data and do we know where our knowledge gaps are (don’t forget the Johari Window’s[1] unknown unknowns!)?

Quick tip: A small tip re the above – don’t be satisfied with yes/no answers, you’ll end up in a right pickle. Discuss each question in detail and make sure you have a shared understanding of each issue and that you can provide a succinct answer to each question (that’s not a yes or no!).

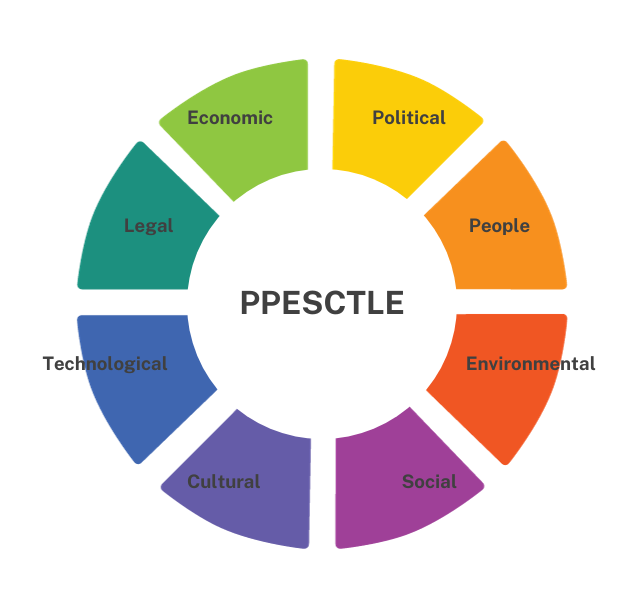

Introducing the PESTEL or PPESCTLE:

The PESTEL analysis is a tool that has evolved since its first appearance in the 1960s as the PEST (political, economic, social, technological) analysis model (Aguilar F, 1967). With policy training work that I do for the Commonwealth Government’s APS Academy they have added an extra P for people that I find very useful. I’ve added C for cultural (that I also find useful!).

[1] Luft J and Ingham H, 1955, Johari Window, multiple online references

There are many ways to use this analysis tool. For this purpose, I find it handy to first identify what evidence-informed data we have under each category. Second, draft the questions we need to ask to identify what we don’t know, to explore the data we are not sure of, and to validate the data we have. Third, identify from whom we could seek the information. We need to engage with a range of stakeholders to get the breadth and depth of information required for the policy at hand. This is called triangulating data. Don’t worry if you come up blank on one or more of the ‘pie pieces’ – this is great! You’re about to learn even more new and valuable information.

Five actions to identify stakeholders:

We need to have five things in place when considering from whom we wish to seek information:

1. We are clear about why we are engaging them.

2. We respect their privacy and their right to decline.

3. We must ensure that they feel safe and secure to engage with us and that we are not causing them any harm by asking them our questions.

4. If ever in doubt of no. 3, we seek ethics advice and or approval before progressing. Trust your gut – if it doesn’t feel right to engage a stakeholder(s), leave them in peace.

5. We commit to ‘closing the loop’, which I call common courtesy - going back to stakeholders to let them know what we have done with the information they have so generously shared with us.

What to explore with stakeholders:

Essentially, there are four themes you need to explore, though this doesn’t mean you’re limited to or have to ask four questions!

1. How the policy commitment is understood. It’s common for there to be many understandings of a policy commitment. If there is significant gap between the purpose of a policy and how that purpose is understood, it indicates work may be required to adjust the policy commitment's wording (with approval from the decision makers).

2. What does good look like? This is a great question to explore how stakeholders visualise what a policy problem being solved, or an opportunity being embraced looks like, feels like.

3. The change that needs to occur from now (the policy issue at hand) to where we want to be (what good looks like). What needs to happen to drive the change.

4. How we will know if the policy has been successful. We need to explore from the get-go of a policy development, the measures and indicators that need to be monitored to identify whether the policy is on track, needs some tweaking or is not progressing as anticipated.

My go-to back up questions:

There are three questions I ask at the end of each stakeholder session:

1. What were you expecting me to ask that I haven’t asked?

2. What else would you like to share with me?

3. Who else should I talk to?

No need for rules:

There are no hard and fast rules about whether you engage with stakeholders individually, in small groups or large groups. You might wish to engage them by specific areas you wish to explore, or you might wish to bring a mix of stakeholder expertise together. You may engage with some stakeholders once and with others on multiple occasions. Again, be clear about how you wish to progress – put pen to paper and map the stakeholder engagement. Don’t fall into the trap by assuming your intended stakeholders will be available or willing to be involved as you planned. Have some back-up plans too.

Identifying the right person to ask the questions:

It's also important to discuss with your team, who is best placed to ask the questions. It’s quite possible you will have a mix of people from your team leading different stakeholder sessions. Consider the expertise of each team member and their rapport with different stakeholders. There are also times where an external party is engaged to do this work. Spend time on planning this too – a stitch in time and all that stuff comes to mind.

Time to pop your curiosity boots on:

Share this blog with your teammates and organise a one-hour session to do your first cut of the PPESCTLE together. At the end, schedule your next PPESCTLE session that may be the whole team, or you might break up the team and compare notes in a third session. Mix it up and make it yours. It’s amazing what we can do with a time limit and over a couple of sessions you’ll be on your way.

In my next blog we’ll look at how to keep decision makers and stakeholders informed of how work is progressing. We want to bring them with us and this too is an important part of our policy craft.